Many, many years ago, as a small child, I was given a compass (for navigation purposes not drawing) by a relative. I was not that impressed at the time. I would rather have had a toy, or sweets, or even money to be honest. Over time, however, I got to love that compass. It came in a nice leather case with my initials on it. It had an inbuilt magnifying glass so I could see the information it provided clearly, and a button on the side so I could fix my position once I had found it. It turned out to be a most useful present which I made use of for many years until it became somewhat superseded by my iPhone (and all the other stuff that modern media provides today to guide me on my journey). Whether or not we make use of such a compass today, I would suggest that we all (individually and corporately) most certainly need to begin this new year by re-evaluating our moral compass?

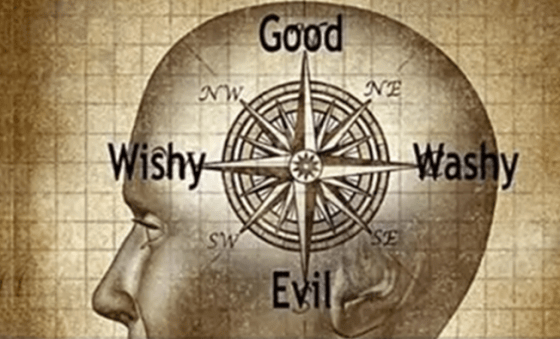

A ‘moral compass’ is a metaphor for one’s ethical value system or integrity that helps us distinguish between right and wrong. Switching metaphors momentarily it functions ethically in much the same way as a plumbline or spirit level might serve a builder-decorator practically. It is often invoked in contexts of decision-making, especially when choices involve moral dilemmas. Just as a compass provides orientation in physical space, a moral compass provides orientation in ethical life much like a navigational compass points north. The phrase originated during the Enlightenment in French physician and historian Nicolas-Gabriel Le Clerc’s book La Boussole Morale et Politique des Hommes et des Empires (The Moral and Political Compass of Men and Empires) published in 1780. It entered English literature in the early 19th century, with notable uses by the American political writer John Taylor in his An Inquiry Into the Principles and Policy of the Government of the United States, published in 1814, and popularised by Charles Dickens in Martin Chuzzlewit, published in1843. Over time. However, its usage has become cross-cultural and the metaphor has been widely adopted in many languages and its meaning has evolved beyond its literary roots being used in modern political and cultural dialogue within journalism, psychology, and so on.

Several factors contribute to the formation of a moral compass, including our personal value system, those core beliefs that shape our understanding of right and wrong, such as honesty, integrity, and respect for others. Then there are our cultural influences, those societal norms and values that we have been exposed to down through the years which can significantly impact the moral framework by which we judge things. Many people also derive their moral guidelines from religious teachings or philosophical principles, which can provide a structured approach to ethics. Personal experiences, including challenges and successes, can also shape and refine an individual’s moral compass over time.

A lack of a moral compass often manifests itself as a deficiency in empathy and integrity, leading to behaviour that disregards ethical standards and the well-being of others. When someone lacks a moral compass, they may struggle to make ethical choices, often prioritising personal gain over the welfare of others which in turn more often than not leads to harmful behaviour and a complete disregard for societal norms. Individuals who lack a moral compass often lie easily and frequently, even when the truth would suffice. This habitual dishonesty undermines trust in relationships and can create a web of deceit that is difficult to unravel.

Another significant indicator is a total lack of empathy, a blatant disregard for others’ feelings. Those without a moral compass frequently show little concern for the pain or discomfort they cause others, often stepping on others to achieve their goals. People lacking a moral compass exhibit inconsistent behaviour, such as failing to keep promises or commitments. This unreliability can be a sign of deeper issues related to responsibility and integrity. Excessive charm can sometimes mask a lack of sincerity or depth in character. Individuals may use charm to manipulate others and as a cover for their own shortcomings, making it difficult to discern their true intentions. A lack of respect for personal boundaries is another red flag. Individuals may disregard others’ needs and feelings, focusing solely on their own desires.

The development of a moral compass is influenced by various factors, including genetics, upbringing, and life experiences. For instance, individuals who experience a lack of empathy in their formative years may struggle to develop a strong moral framework. Additionally, societal influences and peer pressure can also play a significant role in shaping one’s moral beliefs and behaviour. Recognizing the signs of a lack of moral compass can be crucial in navigating personal and professional relationships. Understanding these patterns of behaviour can help us make informed decisions about whom to trust and how to engage with others. By fostering empathy and integrity, we can work towards developing a stronger moral compass, benefiting both ourselves and our community.

Over the years we have all (individually, and corporately) developed some kind of ‘value system’ or ‘set of beliefs/attitudes’ or ‘world view’ by which we make the various judgment calls we make along life’s journey. It has become fashionable, if somewhat questionable, in recent years (partly courtesy of Oprah Winfrey) to individualise one’s value system, so you often hear people speaking about ‘my truth’ as though that validated the particular view they were expressing. It does not! ‘My truth’ can actually be an expression of personal bias, microaggression, or complete nonsense! Organisations such as political parties, clubs of one form or another, churches, etc., also have corporate value systems enshrined in their manifestos, constitutions or mission statements. Whether personal or corporate, however, I would suggest that our value systems need to be re-evaluated at regular intervals if they are to retain any kind of relevance and worth. Society is constantly changing and we are (hopefully) changing as we continue to mature.

There is, of course, a big difference between a value system, set of beliefs, world view and a moral compass. The particular set of values, beliefs, views which we use to govern the direction of our lives or organisation may actually be far from moral. The ideological framework that shaped National Socialism in Germany under Adolf Hitler, for example, wasn’t just a political programme, it was a world view that sought to reshape culture, society and morality according to a rigid racialized hierarchy. The subsequent Holocaust claimed the lives of millions of people targeted by Nazi Germany because of their identity, beliefs or perceived undesirability. Around six million Jews were murdered across Europe together with thousands of Roma and Sinti people, people with disabilities, Poles, Serbs, Soviet prisoners of war, Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals, as well as others deemed ‘political opponents’ or ‘subversives’. Experience shows that if we want a trustworthy guide for making moral choices, it is best not to rely solely on our own instincts. After years of hanging wallpaper, I have learned that relying on a plumb line is much more precise for creating straight lines than simply trusting your eyes.

So where should we look best to find our moral compass? A question like this has real weight, yet it remains one people often rush past, even though everything else in life quietly depends on it. A moral compass isn’t something we discover like a buried artifact. It is something we calibrate – again and again – by paying attention to a few deep sources that shape who we are becoming. I would like to suggest four areas worth considering, each with a different kind of clarity.

1. Our deepest convictions, not our passing feelings. Feelings shift with sleep, stress, or circumstance. Convictions are the things that remain true even when they cost us something. A good test is to ask ourselves: What would I still stand by if no one applauded me for it?

2. A trusted tradition or narrative larger than oneself. This frequently encompasses the study of Scripture, the Kingdom perspective introduced by Jesus, and the theological paradigms I have examined in recent years. Traditions do not give us a script; they give us a horizon. They help us see beyond the narrowness of our own moment.

3. A community that tells the truth. Not a crowd that flatters us, but people who genuinely challenge us; who tell us bluntly when necessary: ‘That does not align with who you want to be.’ Moral clarity grows in relationships where honesty and grace coexist.

4. A ‘lived-for-others’ life. Sometimes the compass becomes clearer by looking at the fruit of our choices. What leads to wholeness, justice, and life for others? What leads to diminishment, harm, or self-deception? Jesus said, ‘by their fruits you will know them’ (Matthew 7:20), consummate wisdom that is as psychologically accurate as it is spiritually profound.

This is an ongoing process and we need to recognise that these various sources interact with each other within the reality of the ‘now/not yet’ tensions of everyday life. Nevertheless this framework actually has a lot to say about how moral discernment works in a world – if we take the teaching of Jesus Christ seriously – that is both redeemed and still being redeemed. So… Where do you feel your own moral compass is pointing – or wobbling – right now?

In recent years I have personally come to look to the Person, Work and Teaching of Jesus Christ as the lens through which I find my own moral compass… the lens through which I judge everything else. Mindful of the words of the Psalmist: ‘I have set the Lord always before me’ (Psalm 16:8) I make it a daily practice to do this ‘by keeping our eyes on Jesus’ (Hebrews 11:2) and ‘considering’ (Hebrews 11:3) how Jesus would see and respond to the questions, circumstances and challenges facing me right here right now. John Newton’s words (written many years ago) still carry tremendous weight:

What think you of Christ? is the test

To try both your state and your scheme;

You cannot be right in the rest,

Unless you think rightly of him.

~ John Newton (1725-1807)

Jim Binney